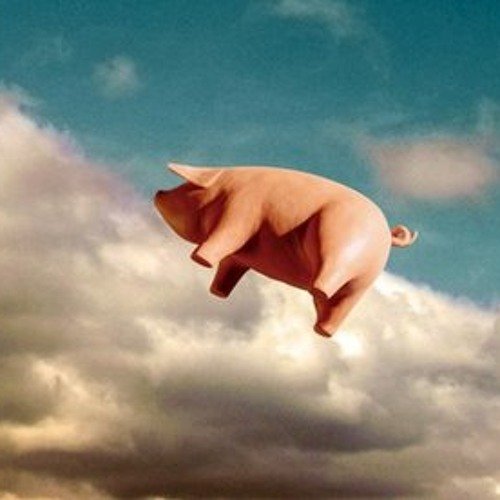

Pigs on the Wing

The force that drives human behaviour and progress is imagination. Rationality tests and validates.

Occasionally glancing up through the rain

Wondering which of the buggers to blame

And watching for pigs on the wingPink Floyd, Pigs on the Wing - Part I, Animals, 1977

The practice of change management, indeed all management practice, has a Newtonian view of time that is useful but insufficient. In this view, the measure of organisational change is progress against a plan to achieve a desired end state. It is rational, assumes the path to the desired end state is clear, and the organisation's position in time and space can be fixed through accurate measurement.

This view is in our theories and models of behaviour, organisation, and how we influence both. Theories and models are essential for managing change, but we need to understand how these models arise, their purpose, and perhaps most importantly, when they become dangerously unhelpful.

All theories and models help us bring order out of chaos by providing ways for us to access shared meaning and communicate effectively. They connect and orient. For example, Chess is often a helpful representation of competitive organisational strategy. It can be a valuable starting point for framing our thoughts on action and reaction or sequencing actions to achieve an outcome. However, as a representation of reality, it has limitations. There are no half-moves in Chess, nor is there the option of adding a row to the board. In real strategy, the rules are not as fixed.

Our theories and models don’t just appear; they come from the imagination and actions of the human mind. They are shaped, developed, and refined by people working together. Ultimately, individual imagination is the catalyst.

The available information is funnelled through personal perception, experience, and speculation filters. This process flattens and simplifies to provide a representation of reality. Once we have a model, we can test, validate, and adapt it. Facts alone, without the organising synthesis of a theory or model, are isolated and contribute little to our understanding.

Our theories of behaviour, work, and organisation will always be partial. The pursuit of meaning by a straight and narrow path rarely yields insight. The path of organisational change winds, varies, and occasionally doubles back on itself.

Our organisations are bundles of layered historical accidents—the product of actions that accumulate over time. We accommodate variance and discontinuity in our experience by developing ingrained habits of practice that are the best fit to achieve the outcomes we have set with the materials we have to hand. Our rationally developed models of change and tightly controlled project-managed actions are not designed for the shape of this particular problem. This gives some weight to the often-quoted statement that 70% of change management initiatives fail. The wrong thinking and wrong tools for the wrong job.

The history of change management is replete with theories and models that have been given existence and permanence divorced from reality. While grounded initially in sound research, these models develop into grossly over-simplified process maps that give managers false confidence that they are in control. The models become pigs on the wing. We would do just as well to look at the application of these models in wonder and follow the course they take out of idle curiosity.

The synthesising imagination at the source of theory development and model building must stay with us through implementation. The same imagination that generates our theories and models (our knowledge) should be alert to the limits of applying them. Unfortunately, it is easier to standardise, program, and catalogue our experience to access comfort and certainty.

We need to be sceptical about the number of facts we know. We should be mindful of the effort and time required to reshape historical accidents and ingrained behaviours. Our thinking, methods, and practices should reflect the nature of the problem rather than shoehorning the problem into the most easily accessible guidebook for change. This is the more challenging path. It is easier to watch pigs flying.